How to Teach Words to Humans

Teaching vocabulary is not nearly as complicated as school makes it seem--unless you try to disconnect it from reading.

Vocabulary is both the foundation and a subset of something every parent wants to see their child doing: reading.

Grammar school is called grammar school for a reason. It teaches the “grammar” of subjects, i.e., the language particular to those subjects. Despite the largely fruitless effort to make every subject taught in elementary school “skills-based”, the whole point of grammar school is memorization; the brains of kids that age are geared for just that. This is why people call young children little sponges. They can hold onto all kinds of information. They can’t tell you why you shouldn’t pet a rattlesnake without being explicitly told why, but they can tell you all about one if they’ve seen a picture in a book or read about them. Writing here is very much limited to recall of facts.

Memorized information, i.e., knowledge, opens the door to the logic stage where a child will start to think about how a black widow spider and a rattlesnake and a mongoose and maybe their mean Uncle Joe are all related: they shouldn’t be toyed with. A child’s ability to use logic blossoms in upper elementary grades. Yes, your mileage will vary. Some kids are able to suss out hows and whys earlier and some take longer to make inferences, analyze, and judge. The more knowledge a kid has, the sooner they will be able to begin to do this as their brain has many pieces of disparate pieces of information to connect. Writing at this stage is going to be more about explaining. You’ll see if/then statements, transition words like “thus,” “so,” and “however”, and ordination like “first”, “next”, and “finally”.

Then we hit rhetoric. This is the stage where a student learns to express herself persuasively. Of course, this is built on the the logic stage so that what she says or writes is reasonable, rational, and well-ordered and, obviously, the grammar stage where she employs all that hard-won knowledge so that her arguments are not mere sophistry.

Without the grammar stage, the place where the kid picks up the words requisite to understanding subject matter, then the words needed to understand and express the hows and whys of things in the logic stage, and most certainly, the level of diction required to persuade an audience of the rightness of her argument (and, more importantly, to test whether what she believes is, in fact, right), your kid is left unmoored.

That brings us back to vocabulary.

You’re going to hate me for saying this, but the answer is simple (if not necessarily easy): read. Read everything you can to your child before she can read and fill your home with high-quality books (from the library or used booksellers on eBay) when she can read on her own.

How do you determine high-quality? I did it for you, here:

Teaching Younger Children

If you read quality literature to a young child, she is going to learn so many words. You can speed this process if you make an effort to elevate your own diction by sprinkling high-level words in every day conversation with her and with others when she’s present.

How do we magnify the gains from great literature? We add subject knowledge.

I’m not an expert on homeschool curricula, I want to be clear about that. There are plenty of people you can reach out to for help, and I recommend looking for local resources first to connect you with a community of like-minded people.

What I AM an expert on is learning inside (not great) and outside (can be a lot better) of school. So I’m going to give you this one free resource, just to get you started. I truly believe that if I had had something like this as a kid, I would be much further along intellectually myself. Knowledge delivers compounding returns; the more you learn early on, the better off you are in the long-run.

Story time: I really don’t remember learning much in school. My mom reports that I was constantly in trouble for “helping” other students because I finished my work quickly and accurately throughout grade school. Answers were always obvious to me. I don’t remember struggling with anything until geometry in high school, but I had a spectacularly bad teacher who spent way more class time talking about the sport he coached than math. I read voraciously as a kid and that’s what I credit with my academic success. I’d already gleaned most of the stuff we were learning in elementary school, and the rest I could either figure out on my own or bluff my way through. My parents were not overly interested in my academic development, but my mom was willing to take me to the library. I stuck with what I knew and loved: stories.

But as we have established, I am a weird hyper-nerd who grew up in rare circumstances. And here’s the rub: even though I was mostly educated in the late 80s and 90s before school really jumped the shark on enforcement of academic and behavioral standards, I don’t think school was all that great. I spent most of it reading books of my own choice under my desk. My teachers in middle and high school rarely moved out from behind their desks so as long as I got whatever they’d written on the board done they left me alone. This was fine, but it was also a helluvalot of wasted time. Had anyone directly instructed me in actual literature and history rather than letting me float through unchallenging school by dint of what I read on my own in popular fiction, my life would be very different.

So here’s the intervention. If you’re taking the reins on your kid’s education, you can do far better than 7-year-old me because you have free, unlimited access to this gem: The Core Knowledge Foundation.

Education superstar E.D. Hirsch realized long ago that education in American was failing because our schools weren’t imparting what he termed “Cultural Literacy”, the body of knowledge, facts, concepts, and cultural references that people need to effectively communicate and function within our society. Hirsch did the enormous work of gathering this knowledge, laying it out in grade-by-grade format and then, of all things, making it absolutely free for everyone to access. Parents can download the units and Teacher's Guide, review the recommended Teacher’s Guide herself to find the questions and activities that best serve the family’s goals and the kid’s academic level and, (after blocking wifi access), give their literate child the student version to read. Talk, review, write, et voila! your child has a GREAT foundation for additional education.

If you want to go fully screen free — which I wholeheartedly recommend — you can buy the texts and activity books by grade level or homeschool sets by grade level directly from the Core Knowledge Foundation or, if you don’t have a lot of excess cash floating around, used on eBay. (This is not a paid endorsement; I just know Hirsch’s work and think it’s a good starting point for most families.)

Are the materials perfect? Nope. Is it possible you’ll run into something you don’t like about them? Yup. So choose where you want to focus and to what you’ll give shorter shrift. Know that CKF releases this to schools around the nation, so they try to remain neutral, but they’re also doing their best to adhere to all state standards, some of which are less neutral (think California).

The bottom line is that knowledge IS vocabulary. Start with knowledge, and then run with the huge logistical advantage you have over the typical public school. You see, you can help your child experience then apply all this knowledge in real life. You can take your kid to places where she can see and touch and taste and smell these things, a feat schools frequently cannot for multiple logistical reasons. You can pull up videos to help her understand the information and sit with her and talk to her about them (and not let YouTube choose what she learns). You can bring in related storybooks and poems and art and music that will help her understand concepts at a much deeper level. You can take your little girl to a local farm or on a walk in a forest or beside the sea or on a weekend trip to a frontier town so she can see and touch the things the words in her readings represent. When your kid gets really excited about something you can’t visit, you can head to the library and get mountains of books that will allow her to explore the subject in more depth, something no school has time for, no matter how well-meaning the teachers.

And in so doing, you will exponentially increase her vocabulary and, therefore, what she brings to the next thing you study together.

And don’t even get me started on your greatest advantage: the ability to pace your lessons to the speed of your individual child. Oh, what I could do with that gift!

Teaching Older Children

If you have an older child who is not an avid reader, and who may not have a high level of cultural literacy, or who does struggle to read, I’d probably still recommend looping back to Core Knowledge, but hitting only 6th-8th grade units. The Core Knowledge curriculum spirals, which means it revisits previously covered topics, deepening them as a child ages. (Note: if you have a kid who’s behind, go back three years from their grade level. So if you have a 5th grader, start with 3rd grade CK units. Those will be accessible to your child. Please sit near them if you can. A kid with a weak foundation needs non-judgmental, immediate corrective feedback. When you get frustrated or disappointed in his performance, try to keep in mind it’s probably not his fault if he learned little, the schools are that bad.)

Having said that, my travels in the teaching of adolescents have taught me that asking a kid to move through a textbook while using the Cornell Notes process (followed up with the Core Knowledge quizzes and tests) to ensure he holds onto the bulk of his learning may cause a war in your house. Still, I’ll tell you that my children’s summer freedom is conditional on them learning a few topics using Cornell Notes while I track their progress daily. This may be too big of an ask at first, but I’d try. The reason your kid “hates” school is not an actual antipathy to learning. He thinks he’s not good at it, but you can show him that he can be. Pick a high interest topic, print out the reading so he doesn’t get screen-distracted, give him a highlighter and then ask him for a page of Cornell Notes, with a summary. He’s going to get a LOT of topic-specific vocab out of that.

For the kid who refuses, or for parents who are too stressed to take on this fight right now (you can’t avoid it forever though, mom and dad) follow the step-by-step prescription below. Yes, you will still have to fight the screens if he’s accustomed to them or you’ll never get him reading. (If you want to understand why you must cut him off, read my piece On Screens, Schools and Your Child.)

Explicit, Reading-based Vocabulary Instruction

Don’t bother with junk reading of book series your kid already likes like Dog Man and Cat Kid or Diary of a Wimpy Kid, no matter how tempting it is. Your kid won’t grow from it and it emphasizes the idea that reading is unnecessary; that it’s just for fun, not part of the crucible of soul-formation. I’ve got lists of great literature here:

And I’ve got books that are tied to American history, both fiction and nonfiction, here:

You know your kid and you know yourself, so peruse the book lists above. Keep your child’s interests foremost in your mind, but also look for books you’d be willing to read as he does; you’ll have to read them too if you want to get traction. Choose four or five titles and share them with him. It might help if you can actually get physical copies of the books for him to read so he can try a chapter or two.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the many kids who don’t seem to have any interests. They watch videos and shorts and play games but don’t seem to be into anything. Here’s where I get a little sexist. Boys like adventure stories. They like to see other boys do badass things. Choose books that are full of that. Girls tend to like relationship stories that explore emotions. Go with those. Yes, there are beautiful crossover stories like Charlotte’s Web and Little House on the Prairie with strong appeal to both sexes, but if you’re just trying to get a kid interested enough to improve in reading, there aren’t enough of those to choose from.

So how do you go about beefing up an adolescent’s vocabulary? Like this:

Read a chapter of the book you selected in advance. Highlight passages that best reflect your family’s set of values. These are the reasons your kid is reading. Check these for high-value vocabulary words and underline them. Keep it at 10 or fewer per chapter. If you’re just starting out, I’d keep it at 5. For my students, I create handouts with the word, its part of speech, and an example sentence from or related to the story. I’d definitely do this for a struggling reader too. You can prompt AI to do most of this work for you, but you should always, always review what it comes up with before you print it out for your kid. I have seen wonky definitions and LLMs have hallucinated quotes, then cited them as if they actually exist in the text. Ugh. Here’s what mine looked like for Act III of Romeo and Juliet.

Give your kid this vocabulary list and ask him to read the words, definitions, and examples and mark any words that he doesn’t understand with a question mark. Go over them with him. Give him synonyms (words that mean about the same) and antonyms. If you’ve got a great vocabulary, give him lots of related words, explaining the nuanced differences that tell you when you should use one word vs. another. For example, with the words above, explain how beguile is different from manipulate. Those are fun discussions that emphasize the importance of the words we choose in a particular context.

Give your kid the opportunity to practice with the word. Here’s one example of how I do that with a class of 30. Remember to go over it with him. The most important thing you’ll do here is find his errors and urge him to go back to the vocab list you generated when he finishes. DO NOT let him ignore the definition sheet and just guess, but it’s appropriate to offer sympathy if that’s what he does at first. In school, kids get away with guessing and rarely have their misconceptions corrected. A lack of meaningful feedback is why many kids are slow to learn, but it’s one YOU can fix immediately with your own child. And don’t forget to heap on the praise!

I do oral practice after this step too. I ask students to associate characters from movies or plot points from well-known stories with the words above. I do this with whatever novel we’re currently reading, but that might be tough for your non-reading child at first. Start by letting him choose some words and see if he can do a few. You could also prompt him. I might say something like, “Which of these words apply to Cuzco from the Emperor’s New Groove and why? Which ones apply more to Pacha?” Praise, praise, praise anything he gets right and correct his misconceptions, gently, if he misattributes a word. Learning is all about the number of touch points you have with new information. The more times you access it, the more meaningfully you process it, the more likely you are to hold on to it.

Now, let him read. Give him a day or so. It’s important that he get a chance to see the vocab in context and take a breather before he practices with it again. His brain needs to practice remembering the words and he can’t do that unless he’s been away from them for a while. So, once he has read the chapter, send him back to the vocab. He should have a little more familiarity with it after seeing those words in context. Give him a different practice sheet. Again, LLMs are your friend here. Be sure to review what AI came up with for accuracy and appropriateness (and that it doesn’t make the answers too obvious — it does that too sometimes) before you give him the sheet. Again, make sure you go over his answers. And remember to praise him here! This is where he’s doing the harder work of applying the term in context. When he gets something wrong, mark it and make him go back, look at the words he missed and, ideally, explain to you why he got them confused. (You may find out the sentence was a bit ambiguous when you hear his explanation — for an example of that, look at #2. AI, while helpful, is not the answer to human education.)

Now you get to discuss what he read. Get the book and the vocabulary list. Your focus here is not on the vocab, but remember that it will be fresh in his mind after you’ve reviewed his vocab. Your conversation should center on the excerpts from the chapter you think will help him learn the things that will help him most as he matures. Here’s the vocabulary trick: use as many of the vocabulary words as you can during this discussion. Prompt him to use them too, as in, “Do you find Lord Capulet’s behavior abhorrent in this act or would it make sense to you, if you were Juliet’s dad?” I find winking and raising my eyebrows repeatedly when I say the word will make a kid laugh and remember the word; Dad Jokes are a huge advantage here. Note: This part of the process is going to stretch you too. You’re going to have to tie the vocabulary you chose to your discussion and some of the words you selected may not be words you employ very often. One of the great benefits of homeschooling is that you learn along with your kid. It’s the best part of my summer, frankly.

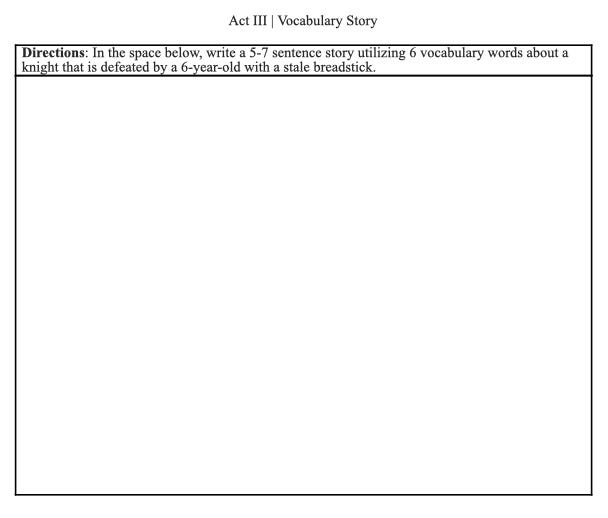

Okay. The final boss: the vocabulary story. (If you’re following my Cornell Notes plan, your kid would be writing a summary of the chapter first before he does this next thing, but I think it’s fun to do this as a separate writing exercise too.) I gave my students the prompt below for Act III of Romeo and Juliet.

Once your child is done writing, read the story quietly. SMILE OFTEN. Let him know you love his story before you correct anything. Read the lines he wrote that made you giggle or that were beautiful aloud.

As for corrections, my students’ most frequent error is to forget to add an adjective ending to change a noun. I see phrasing like “the valor knight” often. Such mistakes offer a springboard for a simple grammar lesson on adjectives and nouns, to teach that only an adjective can modify a noun. And even if you don’t have that language in your own arsenal, you’ll recognize that something is wrong in the way your child used the word. It’s very important that you have him correct his mistakes here. When you see something is wrong, don’t just tell him. Teach him how to fix it and make sure he physically corrects the mistake. Poor practice trains in poor habits; you definitely don’t want to do that.

The last thing that I’d recommend for a homeschooler (and something I should do in my classroom but didn’t this year) is to put these words on a big piece of paper somewhere visible and then make the effort to use them in conversation as often as possible. As much as possible, make it a game. Ask him to use some vocab words to describe his dinner as though he were a restaurant critic or if it was the first meal his girlfriend had made him. There are SO MANY WAYS to play with language; make it playful and he’ll learn faster.

This post was surprisingly hard to finish. I hope you find it helpful. As always, you can reach out to me via chat here if you have any specific questions.

If you appreciate this and believe that my essays, podcasts, and lesson plans will be useful to American families recovering control of their child’s education (even if they can’t fully control their schooling) please consider subscribing to support my work or buying me a coffee and contributing whatever you can. If you can’t afford to help, know that I intend to provide the most important posts to support you in teaching your own children free of charge.

I love this. First, one key component that you mentioned - quality literature. Most books today use "age appropriate" vocabulary and it drives me nuts. Kids will only learn words they hear and use. Older children's books are vastly superior in this regard. Not that modern books are all bad, but for the purposes of vocabulary building, you can't beat something written at least 40 years ago.

Secondly, I'd add that the other simple answer is to use the vocabulary ourselves. Kids model adults and we shouldn't talk down to kids. They understand more than we give them credit for.

Excellent thoughts. I know that my mother read to me a lot from a very early age. I had the extraordinary luck to be a quick learner and an early adopter in this regard. I have no meaningful memory of it, but I was told that I was told that I began reading at a reasonably sophisticated level at three. Since then reading broadly and intensively on some subjects. I wonder how many young children could have had the same luck that I have had had their parents done for them what my mother did for me.