Saving K-12 | Reform #4: Regular Gradebook Audits

Wherein a veteran teacher calls on school leaders to enact five common-sense reforms to address head-on K12's failure to educate.

Concerned parents, teachers, and administrators, this post gets a TL;DR: here is the nitty gritty of my proposal that principals regularly review teachers’ online gradebooks. It’s a form of accountability that is way overdue.

I have only seen gradebook audits when an administrator is looking to get rid of a particular teacher, but even when a principal does take a gander at the gradebook, the information there is rarely used to identify teachers who need support and/or redirection, though it easily could be.

I’ve laid out the case and the process for this below.

NOTE: For those of you following me for guidance on how you can help your child overcome the full system failure that motivated this nearly 5,000-word essay, hang tight: I’ve got something good scheduled for you this week.

Step 4: One site principal will periodically audit each teacher's gradebook to incentivize consistent formative assessment, immediate critical feedback for all students, and clear communication of student performance to families.

Grades are a tool to communicate a student's progress in skill and knowledge over a period of time. Now, due to apocalyptically bad K12 policy, grades have morphed into a proxy for many things: compliance, behavior, school leaders' prioritization of equal outcomes over equal opportunity, and, in too many cases, how demoralized a classroom teacher has become.

This has to stop.

Families are being lulled (lied) into a false sense of security. They are told that their children are learning what they should, in both knowledge and skill, practicing tasks that strengthen both, and studying that information for quizzes and tests with the dual purpose of leaving school with improved executive function and the ability to read, write, calculate, and argue a position as well as a solid foundation of knowledge upon which she can build. Parents believe teachers are properly incentivizing students to attend to lessons then process what they learn in class through practice (i.e., classwork and homework). Parents also believe students are getting and responding to critical feedback on that work, which will, in turn, support achievement on quizzes, tests, and projects.

I do not believe this is accomplished any longer across most middle and high school campuses for a variety of reasons. It must be addressed and I aim to do it here, mainly so no one can say I wasn't solutions-oriented all this time.

The main problem I see is a lack of accountability. The problem: how do you ensure this process occurs consistently across all classrooms at a site with upward of 70 teachers?

Visit every class, every day, keeping track of what's going on in every class?

Nope. Logistically impossible.

Ask teachers to submit daily lesson plans then read them and offer feedback on them all? Also improbably; it’s too labor-intensive for the reviewer.

There's no guarantee a teacher that writes a lesson plan will follow it. I've been at sites whose principals require that teachers submit weekly lesson plans. A small percentage of teachers will break their backs to comply -- but the time it takes to record the many, many components of an effective lesson takes away from the important work of grading and adjusting lessons to respond to student misconceptions or weaknesses.

Then there is the not-insignificant number of teachers savvy enough to send in the exact same lesson plan every week, knowing the odds are good the principal's not really looking, just ensuring compliance with a cursory check of a file folder or his inbox and knowing full well that if he ever calls them on it, they can just say they accidentally sent the wrong file. Then there's the majority who will just stop sending plans in at some point, knowing the principal won't continue checking more than a few weeks beyond the issuance of such a directive. They've seen all this before.

So how do we make sure teachers are teaching the concepts, correcting misconceptions, and incentivizing all students to study the materials on their own to maximize learning?

The answer: Assign a principal to audit teacher gradebooks on a 3-week rotation and provide feedback to each teacher on her practice. (I've also given specific guidelines as to what the individual components should look like, so if a principal needs to take a closer look at teacher work product, he knows what to look for. (If you just want the reform policy, read the "Universal Gradebook Expectations" and "The Gradebook Auditing Process" sections below; this monster is pushing 4800 words.)

Universal Gradebook Expectations

Each teacher's gradebooks should reflect the following:

All teachers guide students as they take notes during instruction and structure their class so that students use those notes as support while doing classwork and homework and in review when preparing for quizzes and tests.

Students will be assigned 2-3 graded practices on the concept covered in notes. Teachers will mark student misconceptions (but not necessarily comment on them all) and return student work, graded, within 24-48 hours, following up with re-teaching and additional practice when warranted.

A low-stakes, closed-note quiz will follow assigned and corrected practices.

This 2-3 assignment ➡️ quiz process will repeat 3-4 times and culminate in a closed note unit test of concepts covered during this process.

Manual Note-Taking

I went into greater detail on this topic in Reform #3: Universal Manual Note-taking, but I'll recap briefly here. Notes are necessary. A strong student will not only take notes in class, she'll also take notes on any readings she does at home. This is rarely required anymore. It's also rare to walk around a school and see a teacher writing notes on the board as she lectures. Instead, teachers project a Powerpoint, which means the students are attending to the slide deck and not the teacher. That's a loss.

Best practices on note-taking are embodied in the Cornell Note format, which involves more than just copying bulleted points off the screen. Cornell Notes give a structure that incentivizes the teacher to pause at natural breaks in a lecture and give time for students to review what they've recorded so far, then write a question that can be answered by the notes. You can improve their recall further by asking students to share their questions out loud and offering feedback on the quality of question. The teacher can use those shared questions to review with the whole class. For an even bigger payoff, show students how to change a "right-there" question to a meta question that forces students to synthesize more of the notes.

In any content area class, note-taking should be an expected activity whenever new information or skills are presented. For math teachers, I strongly recommend pre-creating guided notes in Cornell Note format. Kids use a lot of working memory copying down example equations. Instead, give them the equation with the expectation that they label the directions for each step. This way, you can ensure students are listening to you and watching you work through a problem, getting the steps recorded that will help them complete their math homework later.

If you just give them all the notes, they won't listen to you explain what's on the notes. If you ask them to copy everything, they're looking at what's on the board and not listening or watching you work your way through the problem. Pre-writing notes that they have to partially fill in solves for both of those problems. Yes, it's more planning for the math teachers, but it should mean more focused practice which means less time spent on homework overall.

Administrators frequently decry the number of parents who call them complaining that they have no idea what their child is working on. Parents often want to help, but don't know how. Note-taking means kids are more familiar with the work and have a road map for success that they participated in making, so the skills should be stickier when practiced independently. Notes are concrete artifacts of what’s happening in class, improving school-parent communication and giving parents the information they need to actively support their child at home.

While students compose their summaries, the teacher should walk around, encouraging students to begin, prompting them if necessary, and offering praise and feedback as in, "You left out _____. That's a crucial part of today's work. Where could you slide a sentence in covering it?" Do not let them skip this step. Alternatively, you could ask them to write their summary at the beginning of the next class as a "Do-Now" activity.

Graded Practice (Formative Assessment)

A "Do-Now" at the beginning of each period has two purposes. It is an opportunity for students to review the previous day's work and a hook into the day's lesson. The "Do Now" gives the teacher a moment to take attendance and get ready to teach new concepts, while anchoring students in the work from the day before. This practice should result in a stronger base of knowledge as students gain additional touch points with information through processing and review while completing the "Do Now" task.

The Do-Now should require that students review their notes and summaries from the day before and apply what they learned to the new question. Toward the end of the Do Now time, the teacher should circulate the room with a clipboard, marking off the students who completed the work. Then she should review it with the class, encouraging students to correct any misconceptions they had and add missing information.

The Do Now is one option for a graded assignment as it allows you to check their understanding of the previous day's material after 24-48 hours of "forgetting" time.

Another option for graded practice is the exit ticket. Leave students 5 minutes at the end of class with a carefully constructed question that asks them to tie together the day's learning. Tell students to pack up after they're done with their exit ticket, then have them drop it off on the way out the door.

For both the Do Now and the Exit Ticket, I strongly recommend the following grading practice for simplicity and in order to provide effective feedback for the entire class.

Read the student work. I generally mark the papers in two ways. When I see an accurate statement, I write a check mark next to it. When I read a misconception, I place the sentence in brackets and write a question mark next to it if it's unclear or confused and an ❌ beside it if it's incorrect.

Next, I separate students work into piles by quality: (1) nuanced and clear, (2) comprehensive, and (3) incomplete. The "nuanced and clears" get a ☑️+ on the top and a score of 9-10 in the gradebook.

If the work is comprehensive, i.e., it covers the major components of the topic, I indicate that with a ☑️ and a score of 7-8. A student cannot get this score if they miss any major aspect of the question.

If the work is missing a major concept, it gets a ☑️- (check-minus), which is usually a 6 in the gradebook, but can be a 5 if the student showed little effort.

If the work isn't turned in, it gets a 0; I don't care what the principal says. (Teachers who want to be nicer about this can use a four-point scale so a kid who turns nothing in is penalized less percentage-wise, but it will also penalize the check and check-minus kids with a lower overall percentage. There are no solutions, only trade-offs.)

I'm very specific here because I want anyone reading my gradebook to reckon with the fact that work turned in does not automatically get full points for completion. A gradebook full of 10 out of 10s followed by Fs on quizzes and tests is a huge tell that the teacher is failing to provide corrective feedback.

By giving full marks for every assignment (usually to avoid grading them all, and now, to be fair, often because teachers feel powerless in the face of AI-enabled cheating), teachers set up the kids for failure. Full credit can and should be interpreted as perfect work. A student generally won't look for her own mistakes, so how can she correct her misunderstandings before the test if she keeps receiving perfect scores on practice assignments?

Corrective feedback on each individual's assignment is the most effective way we have to individualize teaching to address student weaknesses in the current public schooling model. Sure, you can let a student choose a project topic, but in my opinion, such forms of individuation require way too much class time when you look at the amount of information students are expected to learn in any given school year. Literacy matters and isn't built on phonics past the 3rd grade; it's built on shared knowledge across a culture which means that knowledge must be transmitted effectively and practiced enough to ensure long-term retention.

Back to grading. The three scoring piles are important to me as a teacher because I want to see 70% or better in the check or check-plus piles. If I don't see that, the concept needs additional teaching and more practice. When a teacher does this right, it's easy to for her to determine when the kids aren't getting it. It makes her decision to reteach obvious. It also makes it clearer to her when she may need to find aother way to teach a concept and reach out for help. THIS IS A WIN, especially in a class like math where the skills stack over time.

I like grading Do-Nows and Exit Tickets because it also gives me the opportunity to support literacy in non-ELA classes. Generally, my Do Nows and Exit Tickets are short essay questions. Occasionally, I'll ask students to create a flow chart to show how ideas or concepts progress or to chart the steps of a particular skill. Both options give me a chance to diagnose areas where poor literacy may be impeding understanding or the student's ability to communicate understanding.

Occasionally, I give students lists of review questions. If there are a lot of review questions, I choose 2-3 to read closely and mark only those with the check-plus/check/check-minus grade. I'm looking for understanding of concepts that will be on the next topical quiz -- because that's where students and parents are going to look first for indications of overall success in the class.

Endless novelty in education isn't necessary and, I'd argue, harms the institution of public schooling overall. Consistency of expectations and assignments has way bigger payoffs than trying to reduce "boredom" which students often express in order to mask feelings of incompetence. Here is a brief menu of practice tasks (i.e., formative assessments) teachers can employ in any subject area and, most importantly, facilitate a quick turnaround time so students can address their mistakes before moving on to a new topic or skill.

Cornell Notes summaries

"Do Now"

Exit Tickets

Review Questions (select 2-3 questions to grade to minimize grading time and provide all students specific corrective feedback)

Regular Quizzes

Students should expect regular quizzes. Quizzes incentivize the student to review their work and the teacher's marks, which helps them retain the information.

Quizzes should always be conducted in class and on paper. I never give open-note quizzes because that sends the messages that students don't need to study. Whether this is or is not the case doesn't matter: student perception that they don't need to study because they can use their notes will drive their decision-making process.

Always announce the quiz the class before and tell them which topics might appear on it; never more than three concepts you've covered during recent instruction. This helps students chunk their review meaningfully in preparation for the quiz. A teacher who uses this process strategically, will also help students study effectively for the unit test over time.

The quiz should be short. It needs detailed grading, so a teacher should avoid overwhelming herself with questions that need her review. Ideally, she offers feedback to help students sort out their personal misconceptions and/or misapplications. Below is an example of the feedback I provide on sentence diagramming quizzes. Most of my students can immediately see where they went wrong. I return the quizzes and they revise their work according to their notes on the quiz in another color ink. They turn this in as a practice assignment and earn a few pints back. This incentivizes them to learn from their mistakes. Allowing rewrites on a quiz for practice points (NOT a retake of the quiz for a higher score) helps the students do better on the unit test.

If a large portion of the class errs in the same way, the teacher should re-teach the portion of the topic students didn't understand.

When teachers give frequent low-stakes quizzes and use them to inform their instructional choices, their teaching improves; assessments are not just for students.

Quizzes and tests should be weighted more heavily in teachers gradebooks. In middle school, my grades are weighted 40% practice, 50% quizzes/tests, 10% Final exam; in High School it's 20/60/20.) This should be school policy; it should not be up to the individual teacher.

Heavier weighting of quizzes and tests is necessary. In too many schools, kids get away with doing only practice, getting full credit for turning it in rather than for the depth of learning they actually demonstrate, failing the tests and somehow, magically, still get As and Bs -- usually because of equitable grading practices and/or pressure from administrators and parents. Weighting of tests and quizzes at a higher percentage means that a student can't skate by copying off her friends or using chatGPT, Gauth, or other student-friendly LLMs. In-class, on-paper tests increase accountability for all stakeholders.

The vast majority of students will not retain their learning without multiple practices, timely corrective feedback, and directed studying. This used to be common knowledge, supported by tradition which is now supported by neuroscience. We need to re-institute this expectation; it's better for all students.

The Unit Test

Every teacher must begin instruction with the end in mind. She should know what knowledge and skills are necessary to understand this portion of her course.

Her quizzes should test student recall of the information she's presented and the skills they’ve practiced. Her practice assignments should give students at least three exposures to the information she needs them to recall. The notes she asks students to take should be a clear roadmap to the unit test. Daily instruction should include recall of prior learning -- which is best accomplished through review of notes and cold-calling. Everything on the test should be in her students' notes, or pulled from teacher provided readings that were discussed and annotated in class, though in upper grades reading will most likely have to be assigned as homework, with structures that hold students accountable for reading. (I love a low-stakes reading quiz or simply checking student annotations which can be as simple as highlighting and marking those highlights with a * or a ? to drive the next day's discussion.)

A student who has attended to notes and lecture and readings, has completed the practice assignments, and studied for quizzes should NEVER be surprised by questions on a test. If a teacher has done her job well, students who have done the work should be scoring Cs or better. (Please read that sentence again: it's a big caveat given the degradation of academic standards across America's schools in the name of "trauma" and/or "equity".)

A teacher should BEGIN her unit by handing out a study guide that clearly maps what students need to know and be able to do. The study guide should be detailed, but not give answers to the test. I go so far as to include a number of possible essay questions (leveled by difficulty and possible grade so students have agency) that I ask students to prepare in advance of the test.

Students are never allowed to use their study guides or notes on the test. It is worth repeating that no matter how a teacher may rationalize an open-note quiz or test, an immature student will see open notes as a reason not to read the material (notes can be copied), not to listen to lecture (why? I'll copy someone else’s notes), or study consistently (don't need to spend time studying when the notes are on my desk during the test). The point of the test IS the studying. Read that again and think on it; you'll get it.

Study guides should also never be fill-in-the-blank worksheets. My study guides direct students back to their notes and readings (which incentivizes careful note-taking/annotation). They should be able to find everything listed on their study guides in their notes and/or readings. Sometimes, when we review before the test, students point out things I didn't cover that are listed on the study guide. When they’re right, I either delay the test to cover the information I missed or remove related questions from the test.

I have known far, far too many teachers who give almost an exact copy of the study guide as their test and all the answers to the study guide in a "review" the day before the test. Those teachers are communicating to their students they not only do not have to listen or do the practice or worry about quizzes, they could miss most days of school as long as they show up the day before the test to get all the information that will be on the test. This is a terrible message and absolutely contributes to absenteeism in your schools. Ask the teenagers you know if they've had a class where the teacher did this. I would not be surprised if they told you many of their teachers do it, though the practice is most common in science and history classes.

The format of the test should be Multiple choice. Why? The teacher deserves a break and the students deserve to get their test back quickly. NOTHING is more incentivizing to a kid then working hard and seeing the fruits of her labor rapidly. My students celebrate their wins when they get their tests back and they are very interested in seeing where and how they got things wrong. They ask great questions after the test and sometimes I realize that one or two of my questions was hot garbage and revise not only their scores, but also end up with better test questions for the next time I teach the unit.

If the teacher has been doing her job of guiding students through notes and readings, offering meaningful practice, providing actionable feedback, and using quizzes to inform her practice and reteach concepts, she shouldn't have to break her back to grade the test.

While I do think the vast majority of the test should be multiple choice, there should be a bit of lifting for the teacher on a few essay questions. (I have my students write a full in-class timed essay with every test I give, but I'm old and salty and have the chops to cope with the grading this entails.)

Most teachers should carefully craft 2-3 essay questions which require students to combine multiple concepts form the unit into one coherent response. As she grades, she should use a simple check mark when a student adequately covers a concept and ties it meaningfully to the topic. This should be relatively quick.

The other recommendation I have is that on each test, the teacher creates a "Brain Dump" area where students can make a bulleted list of information they knew that was not on the test. This can be a place where the teacher uses discretion for students who may not do as well on the multiple choice portion of the exam, but attended to the material covered in class, completed the practice work and studied for the test.

The final test should never be a project or group work. I promise: competent teaching results in students who WANT to take a timed test. They are so proud when their grades improve over time. Tests help build the kind of real confidence that allows students to eventually realize their own inherent greatness. Kids LOVE to know things and be able to do things and generally feel competent.

When school leaders look the other way when teachers give assessments that can be gamed by students, you rob them of the feeling of accomplishment crucial to a happy(ish) adolescence and you disincentivize them from building the kind of self-discipline that is the making of the man.

The Gradebook Auditing Process

This is laughably easy now that you know what you're looking for. Note that you probably can't start it until about 4 weeks into the first quarter of the school year. Also, your school should have a clear policy on how late, missing, and incomplete work will be dealt with that is clearly communicated to staff. Don't leave those things to teacher discretion; loose policy here will result in bad data later.

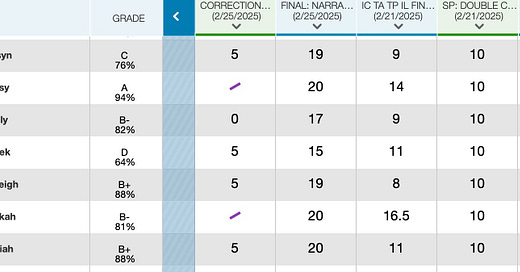

Print out the teacher's gradebook. Highlight quizzes in one color and tests in another. Leave practice assignments unmarked. If there are few quizzes and/or tests, note it.

Create a checklist with these 7 characteristics for whichever teacher gradebooks you're reviewing this period.

Overall Class Grades: Look at overall grades in the class. If everyone has an A or everyone has an F, you have a problem on your hands. You might also have a problem on your hands if the grades are heavily weighted toward As and Bs; that may be a teacher calibrating grading practices to avoid conflict. Continue through the process below to come to an evidence-based conclusion and plan a necessary intervention.

Weighted Gradebook Categories: Does the teacher have gradebook categories differentiated into three categories: practice and quizzes and tests? If not, direct the teacher to correct this immediately and assign weights to her grades before continuing the audit. If you don't know how to do this in your grading program, learn the process and train teachers in it to support clear communication of student learning outcomes.

Assessment Grades: Check the grades on quizzes and tests. If they are round numbers, (15, 20, 25) ask the teacher to share a few assessments with you. Teachers should be offering a majority of objective questions since standards are content-specific. If your district has adopted "mastery-" or "skills-" or "standards-based" grading, understand that skills are based on content knowledge so objective questions should still be heavily employed. If they're sending back essay questions or project prompts only, you will have to determine how they're assigning grades on these assessments: for competence or completion?

Quiz Count: Make sure there are at least three quizzes before a unit test. If not, discuss with the teacher how she's ensuring the students have had enough practice under similar conditions to the test before the actual test.

Practice Assignments: Count the practice assignments between quizzes. If there are at least two, move on. If there are none, that's a red flag that the students are not receiving corrective feedback on their practice assignments or, worse, that they are not being held accountable for completing practice assignments.

Practice Assignment Grades: Check the grades on practice assignments. If they're all full credit or zeroes, you need to have a talk with the teacher. If you realize a number of teachers are using this practice, schedule a training for those teachers. Keep it brief. Explain why full credit on practice assignments is a red flag and will create problems for them with parents (and you) later. Give them the check-plus, check, check-minus system and explain that you expect to see those marks reflected in points assigned in the gradebook.

Some Audit Considerations

Calibrating gradebook expectations will take time. It's going to require difficult conversations with people who are resistant to change because they haven't been held accountable for practices like this for the entire length of their career.

Habit formation has always been the biggest hurdle in education. With the implementation of 1:1 device policies in schools, the battle has become more pitched than ever before as teachers are all too often required to use a tool for learning that many students' brains are trained to see only as a source of entertainment.

It's going to take clear guidelines and accountability to turn this ship around and properly incentivize students to take learning seriously again. Teachers are sergeants on the front-line of this battle. Administrators need to be competent lieutenants.

The gradebook is the map of battle that lays bare each teacher's strategy and tactics. Parents deserve to know whether the teachers' plans have been effective or not in advancing their child down the field toward ultimate success.

The administrator is the party responsible for ensuring that those plans are sound and, if not, issuing the orders and providing the training that will result in them becoming so.

If you appreciate this and believe that my essays, podcasts, and lesson plans will be useful to American families recovering control over their child’s education (even if they can’t fully control their schooling) please consider subscribing to support my work or buying me a coffee and contributing whatever you can. If you can’t afford to help, know that I intend to provide the most important posts to support you in teaching your own children free of charge.

What I wouldn't give to be able to give a "traditional" test outside of my AP course. Or have a grade book where anything below a 60% is failing instead of a C or D. Or take notes more than twice a month without getting talked to about "skills" and how knowledge isn't a "skill" (guess why multiple choice is really frowned upon).

We're not that far from hearing "Welcome to Carl's Jr. Would you like to try our EXTRA BIG ASS TACO? Now with more MOLECULES!"

The worst traits of the Professional Managerial Class can be found in national intelligence agencies and public school administrations.

This grading structure is EXACTLY how I remember my middle and High school years used to be! Especially for my AP classes, there was more work but still measured along these lines. I went to Blue ribbon schools (IS/IB school) and a college prep STEM high school.

When I checked on the schools in my current state, they are nothing like how I remember. All work is done on their Chromebook.

I especially liked your mentioning of note taking, as I was just this past week thinking of how to teach my 3rd grader (by age, she's in 4th grade work and reading at an 8th grade level) how to take actual notes. Since we homeschool, there isn't as great a need to take notes because I know already where my kids are weak and where they are strong. We also constantly do oral review of their subjects but my eldest is very quickly marching through the grade levels. I think I will implement some form of note taking in her history books study, as I see more assignments being done via reading a section and referring to that section for the answer. She goes by memory, my kid got my brain but my brain now is not so academically strong! Have to poke through my old college notes and see what my note style was! 😄