Learning How to Learn

Cornell Notes offer the biggest bang for the buck when it comes to processing new information, i.e., learning. You don't need to scour the internet for worksheets, I promise.

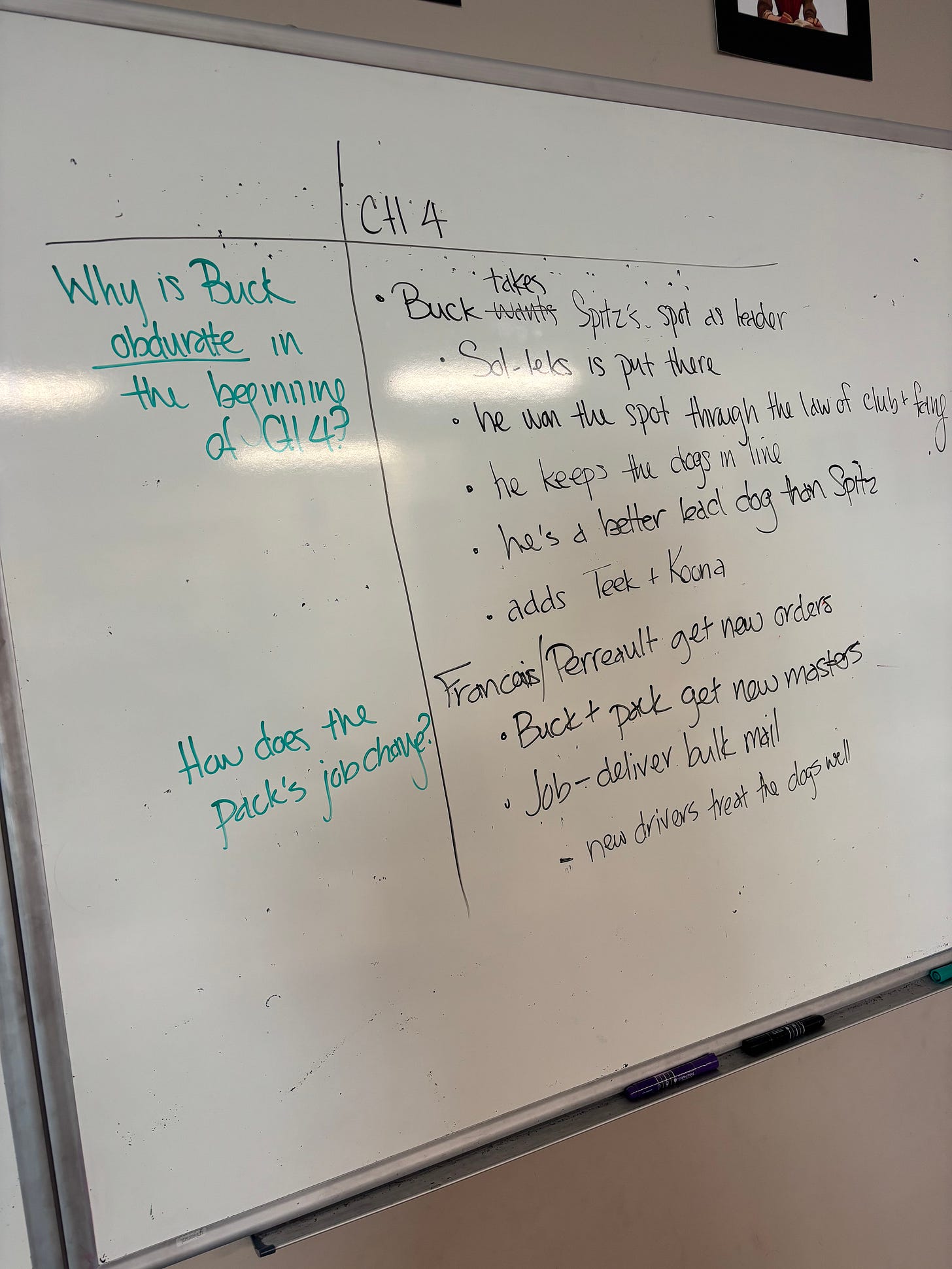

One of the best compliments I get from any student — especially when it comes from a student with learning disabilities — is, “I learned a lot. Your class is hard, but somehow it’s easier to learn in here.”

I wish that was just down to my personal brilliance, but it’s not. It’s because a few years ago after a dalliance with neuroscience, I adopted Cornell Notes for my classroom and explicitly taught students how to use them.

Cornell note-taking (plus the Feynman test) are pretty much the only paper-based activities you need to educate a child at home. The Cornell Notes method is the best processing method I’ve come across in 23 years of teaching. If you can pair Cornell Notes with an end-of-unit written assessment (more on that coming soon), it’s highly likely your child will be light years ahead of his peers.

How do you do this at home? Let me walk you through it.

What are Cornell Notes?

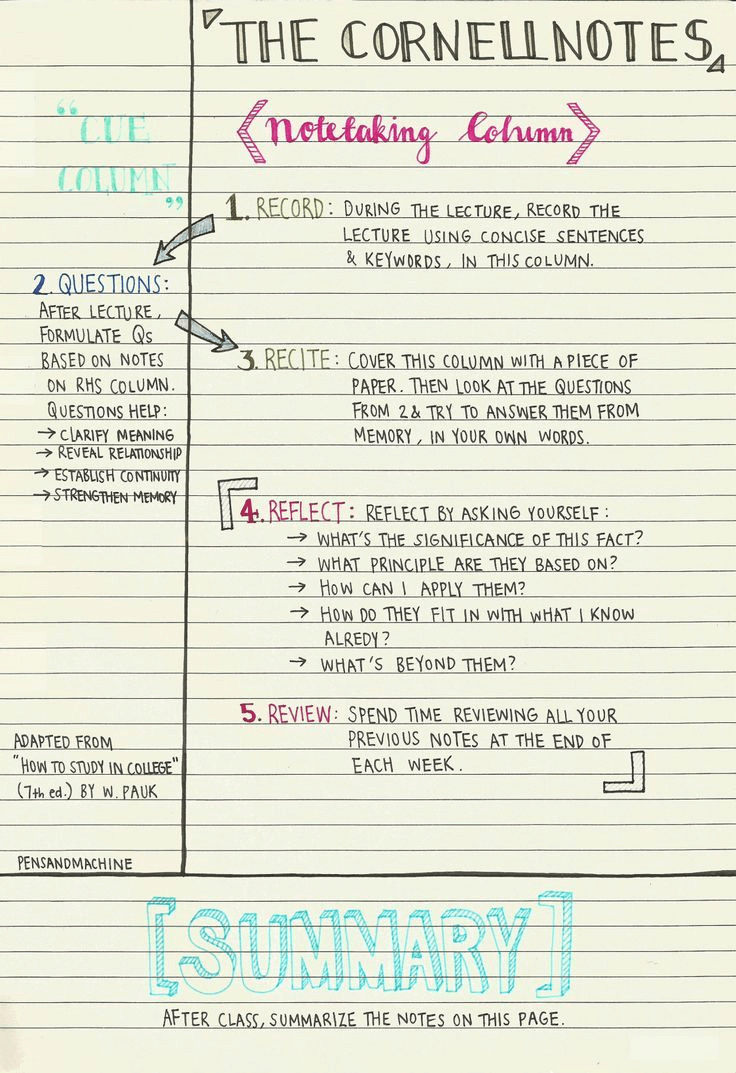

First, what the heck are Cornell notes? Here’s a handy image for you to get familiar with before I explain. This image is titled, labeled and goes step-by-step through the process. Take a minute to read through this, and then I’ll explain.

Okay, so if you read through that, you can see that this is a pretty advanced breakdown, probably for college students, so let’s scale it back some.

You start with paper. Easy enough, right?

Then you separate the paper unto unequal columns, one much larger than the other. Why? Because the chungus on the right is for your kid to record his takeaways from the reading.

I can hear some of you objecting already. Wait a second, DT. That diagram says this is for lecture. I’m not lecturing. And why do I have to make my kid take notes on what he reads? Can’t we just read?

Oh ho ho. It seems we have just stumbled upon one of the main reasons our own K12 years bore little fruit. You and I did just read… and promptly forgot. We were sometimes required to answer a few comprehension questions after reading, the necessary text often helpfully bolded or italicized in our textbooks. So we didn’t actually read, we just scanned the text to get our homework done. We missed the connections that a good writer can help us make — which improve the strength of memory — by blowing through the text.

Today, in schools where kids are given tablets or laptops, students use AI to skip even scanning the text, so if we actually want our own children to learn, we’re going to have to go medieval on their butts, or at least head back to the 1950s with Dr. Walter Pauk, who invented the process of Cornell note-taking when he was a TA at Cornell University.

Start by selecting the information you want your child to retain. This summer, I’ll be training my 11-year-old. (He’s on his way home from grandma’s house right now, so we’ll get started bright and early Monday morning.)

This is how I’ll go about it.

Reading Is the Thing

While I could lecture in history and literature, I’m not going to. I’m going to teach my kids that physical books, carefully chosen, are a better source of information than somebody whose CV I can’t properly vet. Reading also helps us focus on the task at hand by minimizing distractions. I know YouTube can be a good tool, but for younger kids, it’s a distraction machine. Plus taking notes from video is tough unless you’re adept at note-taking already.

First, I’m going to walk my kid through the text. I’ll point out how it’s organized. Let’s look at the history book he’ll be using (and the one I’ll be reading to my 7-year-old).

For history, I’m going to keep this work very simple. He will have a single spiral bound notebook and we’ll separate his notes by unit. His first unit is on the Renaissance. I’ll have him read through some background on the medieval period and maybe give him a few notes to provide context for this topic, but then he’ll be responsible for reading and highlighting the important ideas from a section like this one.

Highlighting a textbook? Heck yeah! I buy used books (eBay is your friend) so that my kids can write in them. Well, then why does the kid need to take notes if he can highlight, DT? I can already see I’m going to have a full-blown insurrection on my hands for asking my kid to work through summer!

Because handwriting leads to increased brain activity, with positive effects on learning and memory.

My son will annotate the text and then use his annotations to write Cornell notes to cover the What, Who, Where, When, and How/Why of each unit. To learn that basic set of facts is his primary task and what I’ll be looking for in his notes.

He’ll start by reading these pages. After the first reading, I’ll ASK him:

What was the Renaissance?

When did it happen?;

Who was involved?;

Where did this happen?;

How did the Renaissance play out?; and, most importantly,

Why does it matter?

If he can’t answer all of these questions from the information he highlighted, I’ll direct him back to the text to find the missing pieces. His answers to these questions will become his notes.

So, within the first contact with this information, I’ve sneakily tricked him into reviewing it multiple times.

First reading.

Answering the 5 W questions orally.

(Possible) If he can’t answer, review.

The Notes Section

Once he has verbalized answers to these questions, I’ll have him look back through what he highlighted and make a pencil mark next to what deserves to be recorded in his notes. (4th contact).

Then we get to the actual writing down of what he’s highlighted and deemed important. He’s going to do that in the Notes section. He’ll use bullets, and I’ll teach him to indent if he’s writing a sub-fact that he found personally interesting (which I’ll also encourage him to do). This will give him a fifth contact with each piece of information.

The Cue Section

After he’s completed the note section, I’ll ask my son to look again at each piece of information he wrote down and compose a question that is fully answered by that information. He’ll write each question beside the notes that answer it. The purpose of this alignment is so that when he reviews, if he can’t recall the answer, it’s literally right there.

The process of creating cue questions will be his fifth contact with the information and, importantly, an opportunity to process the information in a different way. A student who has to transform facts into questions must clarify what he understands. When he gets better at discerning the most relevant facts from details, writing cue questions will help him identify connections between seemingly disconnected facts.

This is where we really start to see memory stick. It’s when you DO something to change or manipulate the information in your own head that recall becomes fast and easy. There is labor in learning. That labor builds memory. I know my students are really starting to “get” a concept when they can look at a topic and write a question that forces recall of more than one fact at a time. For instance, if we were studying, say, The Little Red Hen, a student could ask a question like, “What was the first thing the hen asked for help with?” This is a fine question, but you know they’re really engaged when they get to the bottom of their notes and ask a question like, “Was the little red hen selfish?”

That’s a higher level of thinking. Don’t be discouraged if your kid can’t do that right off the bat. Let them get used to asking “right there” questions in their own notes.

Your next job will be to review the questions with your child after they’re written down. This is the 6th contact your child has with this information. Ask him to read his questions to you. If you know the material — and you should read whatever he’s reading too so you can help him — help him correct questions that are weak.

I always ask students to volunteer their cue questions and give positive feedback for any that are directly answered by the notes. When they’re not very good, I ask the class how we could make the question better, which usually means how we could change the question so that it’s answered by the notes. So back to The Little Red Hen. A student might ask a question like, “Why didn’t the other animals help the hen?” That question isn’t answered by what’s in the text. Your kid may recognize that the cat and the duck and the pig are lazy, but the text never directly says that. If it’s not in his notes, it shouldn’t be a cue question.

As your child improves in this process of determining the key aspects of the text, you can also encourage him to write complex questions that cover more than a single piece of information, but you’ll definitely need to help with this at first. Feedback is critical to overall performance. You’re doing a hugely important job by offering it for two reasons:

So that he can learn to take corrective feedback as a positive and

So the he is reinforced that he is on the right track.

As you listen to him read out his cue questions, your primary job is to make sure your kid isn’t missing answers to any of the five key questions. If he is, have him go back. If the piece is complex, e.g., there is more than one “who” or “what”, etc., you may have to have him go back and write more notes, but what you’re teaching might be the most important (and, in public schools, most often skipped) skill: discernment. It’s easy for kids to get stuck in the weeds. Don’t let them. Stick to the primary facts, though if your kid is having fun, details can be discussed and noted too, but this is where you teach them primary vs. supporting facts.

Always be on the lookout to level them up and ask a more difficult question that requires them to connect information. When I ask questions that I know might be beyond a student’s capacity, I preface it with, “This is tricky, but what do you think this means?” And when he tries, as long as I can see the attempt was honest I give them some version of “Not quite, but I can see your train of thought. Good attempt.” If they get it right, you have more data to push further in the future. If they shrug and say, “I don’t know” you can either let it go, or try to break the question down into something more manageable. Don’t be too critical, but make sure they know you expect them to improve over time as they learn more.

Now you’re at contact 7. Take his notebook from him and tell him it’s quiz time. Ask your child the questions he wrote down in the cue section of his notes. Here’s the thing: he’s going to be able to answer them, and he’s going to feel really good about that. If he can’t answer one, give him back his notes with no judgment and ask him to find the answer there. (That’s another contact!) In doing so, you’re teaching him that his own notes are a valuable resource for studying. When he takes good notes, he doesn’t have to go all the way back to the text and read through the whole thing again.

Many students see notes as a heavy upfront investment, but when the process is mastered, they improve learning overall and will vault a student ahead of kids who rely on a teacher (or an LLM) to tell them which iinformation was key and which was a supporting detail.

The Summary

After you've reviewed and separated big ideas from supporting details, your child will write a summary of what he learned. This is the eighth contact with the information in one session.

If your kiddo is young, you’re going to want to give him a sentence starter to help him write his paragraph.

The Renaissance was _____.

“The Little Red Hen” is _____.

Then have him write the rest of their who, what, when, where, how, and why it matters answers as a paragraph of complete sentences for someone younger. This is important. Tell him to imagine that he’s explaining to a kid who’s 3 or 4 years his junior. This forces your child to reshape the information in his own head, to break it down and reconstruct it for a less knowledgeable audience. This is where real, deep learning can occur. It will also help diagnose any areas of confusion or vocabulary he doesn’t fully understand. It might send him back to the text for answers. That is a great outcome (even if it annoys him).

When he’s finished his summary, have your child read it out loud for you. Reading aloud allows him to catch grammatical errors in his writing. If your son doesn’t catch one of his mistakes as he’s reading, stop him and help him address the error. I’d also review spelling when he finishes reading to you. Address any errors there by circling the misspelled word and helping him rewrite the word correctly.

And here’s your final step, which may sound silly if he’s an adolescent, but do it anyway: when he’s all done with his assignment, put a big old smiley face on it (extra points for cheesy teacher stickers or scratch ‘n’ sniff), tell him you’re proud of him, and give him a hug. That positive reinforcement matters more than you think. If you really want to level up, get grandma or grandpa or a favorite uncle on FaceTime, have him read his summary to them and praise him to the heavens with, “Wow, I never knew that!” or “Thanks for reminding me about that.”

So, besides having eight opportunities to engage with the information you want him to learn, Cornell Notes also allows you to sneak in lessons in composition, in grammar, mechanics, and usage, and in public speaking. Winning.

Review

You must forget to learn. That sounds weird. Allow me to explain.

Learning is the ability to recall information. In order to recall it, you have to forget it. Before you review, you must allow your child time to forget. If you’re doing this at home, save review of the material for at least a day. Begin every day’s session with a review of prior material; this is why having a single notebook for each subject is helpful. Go back a few pages, not just one, and ask those cue questions, then move forward to the more recent material.

Kids love to show what they know. They feel real joy when they get things right. Case in point: just checked my eldest’s sentence diagramming skills. Even though he whinged about me making him do it during summer vacation, the fact that he remembered so much of what I taught him two years ago put a smirk of confidence on his face, try as he did to hide it from his annoying mom.

If you review with your child, you’ll experience the joy of watching his face as his brain works to bring back ideas from preceding days’ work. When he fumbles, you can prompt him using his notes. If you’re familiar with the material, you can ask him bonus questions — just be sure to gear them appropriately; you’re building his confidence here. Don’t try to stump him.

The traditional method of review using Cornell Notes is for the student to use the notes on his own, simply covering the notes section and asking himself his cue questions. If you can’t do it with him, delegate this job to a literate younger sibling; they love it too and they might accidentally pick some things up as they try to catch out big brother/sister.

The Notebook

Tonight my son is going to an end-of-year Burn Party. I’d never heard of one of these before, but it’s a tradition among the students at his new school. The students take all their work from the year, light a huge bonfire, and throw it all in.

This is a dagger to a teacher’s heart. My son wants to go and I want him to have fun, but obviously when he told me about it I was dismayed that he put such little stock in his work this year that he would want to watch it all go up in smoke.

Then I went into his room to dump his clean laundry on his bed.

In several open folders there lay disorganized piles of notes, the Cornell Notes I’d taught him to take but which most of his teachers this year didn’t require.

He did it anyway.

The notes aren’t as organized as I’d like them to be, but they were separated from the worksheets and one-question quizzes and multiple choice tests from his school year. Those got packed into his backpack and are headed for the bonfire.

The notes, apparently, will stay in his folders in his room.

The work matters to him.

The knowledge matters to him.

I hope that your family can use Cornell Notes to make the process of learning mean more to your kids too.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: If you try this but need additional support, feel free to head on over to my chat (linked here) to share your questions, comment below, or shoot me an email. More content teaching the basics of teaching and how I’ve found success with my students and my children will be coming all summer long.

With warm regard,

DT

If you appreciate this and believe that my essays, podcasts, and lesson plans will be useful to American families recovering control of their child’s education (even if they can’t fully control their schooling) please consider subscribing to support my work or buying me a coffee and contributing whatever you can. If you can’t afford to help, know that I intend to provide the most important posts to support you in teaching your own children free of charge.

I love this method. A decade ago I was in university level courses trying to “develop” my own system for this using colour coded highlighters and question and lecture summaries in the margins of lined paper. It was so complicated and necessitated specific coloured markers. If only a teacher would have let me know this existed. I learned the Cornell method a year ago and now use it all the time!

Excellent presentation on how to get the most out of Cornell Notes. Thank you. I'll be using your advice.